Optimising LLM Performance

A discussion on a few techniques to maximise LLM performance.

Contents

A Framework for understanding optimisation

The recent developer conference hosted by OpenAI offered a deep dive into enhancing the capabilities of large language models (LLMs). The presenters, John and Colin, shared their insights on optimising LLMs.

You can watch the video here - I encourage you to do so!

Optimisation of base models can be a critical step on the path to Production. A base model may show promise in a specific application but may lack consistency in a desired behaviour or knowledge to warrant its deployment.

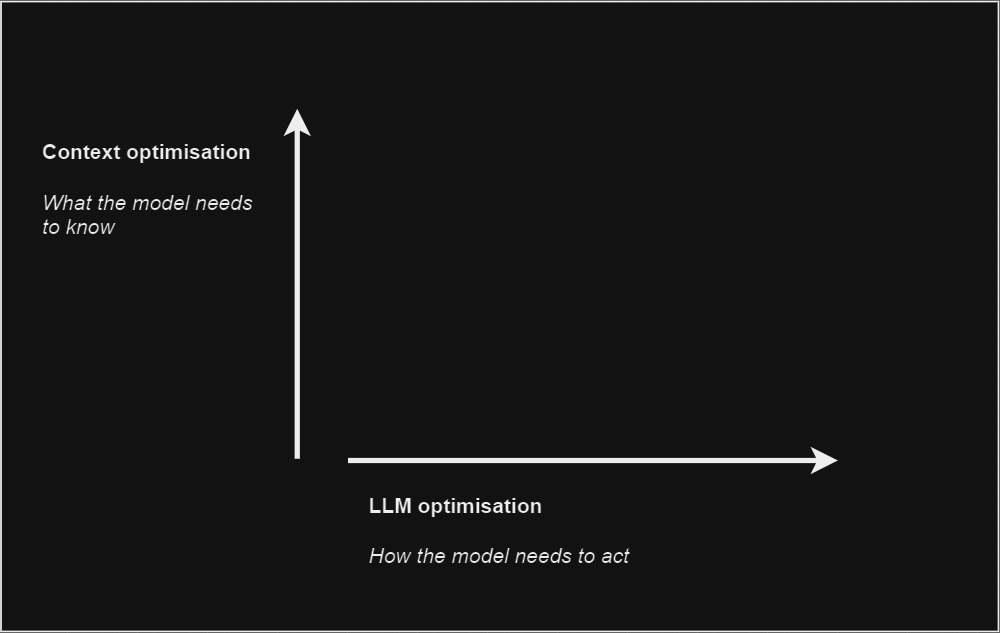

The optimisation approach will depend on which aspect of the model needs improvement. John and Colin from OpenAI propose two primary dimensions of optimisation.

Is it the context that needs improvement—that is, what does the model need to know? Or is it the model itself that requires optimization—that is, how it needs to act?

Graphic adapted from OpenAI’s presentation

For example, a base-model LLM will fail to generate a report on the most recent market trends because it doesn’t know them. Why? Because they were never present in its pre-trained knowledge. In cases like this, the model is said to need context optimisation.

Base models might not consistently follow instructions when the model is required to output particular formats or styles or requires multiple steps or complex reasoning. Some examples of these use cases are generating code from natural language or extracting structured data from unstructured text. In these cases, the model itself requires optimisation.

Using the framework for maximising model performance

Understanding model optimisation in this framework can help identify whether the issue is a context problem or an action problem. Once this is understood, appropriate techniques can be applied.

In the case of context optimisation, Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) is likely a good start. To optimise the LLM itself, consider fine-tuning.

Of course, in other cases, a combination of optimising how a model acts and what it knows will be required.

Graphic adapted from OpenAI’s presentation

Start with prompt engineering.

In either case, prompt engineering is the best approach to start with, as it offers a quick way to test and learn what dimensions should be optimised and sets a baseline for further improvements.

This stage is as simple as starting with a prompt. Then, consider adding a few shot examples (for context issues) or employing a few shot learning (for acting issues). If this yields improvements, you’ll have a good baseline from which to iterate further.

What are few-shot examples?

Few-shot examples refer to the specific instances or data points that are used in the process of few-shot learning. These are the actual samples from which the model is expected to learn or generalise. In a practical sense, if you were providing a machine learning model with few-shot examples, you would give it a very limited number of examples per class from which it needs to learn.

What is few-shot learning?

On the other hand, few-shot learning is the broader concept or methodology that involves training a model to accurately make predictions or understand new concepts with only a few examples. Few-shot learning is particularly relevant when the goal is to develop models that can generalise well from limited data—something that is especially challenging and important when large datasets are not available or when trying to improve model adaptability and efficiency.

Is it a context issue?

Prompt engineering alone is unlikely to be sufficient in more complex use cases, and it doesn’t scale well (remember, we want a Production-grade solution).

If prompt engineering has revealed a context issue, optimising with RAG is a logical next step. For an overview of RAG, see this article the following article (or skip to this part of the video).

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

RAG is typically good for introducing new information to the model, updating its knowledge, and reducing hallucinations by controlling content. If done correctly, the model will act as if it is explicitly amnesic to everything it was trained on while still retaining its implicit intelligence. In other words, the only knowledge it explicitly has is what has been provided in the RAG implementation.

Simple retrieval

Adding a simple RAG retrieval will ground the model in the desired context source. Embeddings and cosine similarity algorithms can provide the model with access to a repository from which it can pull data, for example.

Cosine similarity algorithms measure the cosine of the angle between two non-zero vectors in a multi-dimensional space, providing a metric for how similar these vectors are.

Other RAG options

Other, more advanced RAG options include Hypothetical Document Embeddings(HyDE) (with a fact-checking step). HyDE is essentially a technique where, instead of using the question’s vector to search for answers with an embedding similarity, a HyDE implementation will employ contrastive methods, generate a “hypothetical” answer in response to the prompt, and use that “made-up” answer to search for context instead.

HyDE techniques can be helpful in cases where the model will receive questions that lack specificity or easily identifiable elements, making it difficult to derive an answer from the integrated context source.

HyDE won’t always yield good results. For example, if the question is about a topic that the LLM is unfamiliar with - such as some new concept that was not present in the pre-trained knowledge - then it will likely lead to an increase in inaccurate results and hallucinations. The reason is that if it doesn’t know anything about the topic, the hypothetical answer it created to retrieve context will have no basis in reality…a hallucination, in other words.

This is probably why OpenAI presented HyDE in the video with the + fact-checking step!

RAG evaluation

It’s important to remember that adding RAG to a solution creates an entirely new set of challenges. As John points out in the video, LLMs already hallucinate on their own. If the context the model uses to ground its responses is fundamentally or systematically flawed, understanding whether the solution fails because of the RAG integration or an inherently hallucinatory trait within the model will be challenging. For this reason, evaluation frameworks are crucial.

The video mentions an open-source evaluation framework called Ragas from Exploding Gradients. Ragas measures four metrics: two evaluate how well the model answered the question (Generation), and two measure how relevant the content retrieved is to the question (Retrieval).

The Generation metrics are:

Faithfulness - a measure of how factually accurate the answer is.

Answer relevancy - how relevant the generated answer is to what was asked.

The Retrieval metrics are:

Context precision - The signal-to-noise ratio of retrieved context.

Context recall - Can it retrieve all the relevant information required to answer the question?

Context precision is particularly useful because providing RAG implementation with more chunks of data potentially containing relevant context doesn’t always work. John mentions a paper, Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Large Contexts, which explains that the more content given, the more likely the model is to hallucinate because LLMs tend to “forget” the content in the middle of a chunk. Not surprisingly, this is reminiscent of the Serial Position Effect observed in human cognition, which is the tendency to remember the first and last items in a list better than those in the middle. This effect has been well-researched in psychological science and can form part of the basis for various cognitive biases.

On the other hand, context recall helps to understand the utility of the search mechanism. A common misconception with RAG implementations is that it will always find the proper context. But there is a fundamental constraint to remember: how many tokens can that context window accept. If it were possible to pass the entire context source to the LLM for each prompt, then context recall would never be an issue. But the computing power required for even a modest context source would make this unviable.

The missing piece to consider is that the prompt is parsed into some search function, and it is the search function that surfaces the (ostensibly) relevant context. It is this surfaced context that the LLM relies on. So, evaluating context recall will help identify if the search process is surfacing up the most relevant context. If not, the search function may need optimising, such as re-ranking or fine-tuning the embeddings.

Graphic adapted from OpenAI’s presentation

Is it an actions issue?

If the required optimisation is related to how the model needs to act, then fine-tuning will likely be a good approach. Fine-tuning “continues the training process on a smaller domain-specific dataset to optimise a model for a specific task”.

Fine-tuning

Fine-tuning is equivalent to teaching a general knowledge worker a specialised skill. It can drastically improve a model’s performance on a specific task while also making the fine-tuned model more efficient (on that specific task) than its corresponding base model.

Fine-tuning is often more effective than prompt engineering or few-shot learning because a much smaller token count inherently constrains these techniques. Only so much data can be put into the context window, whereas in fine-tuning, exposing the model to millions of tokens of specialised data is achieved relatively easily.

In terms of model efficiency, fine-tuning provides a way to reduce the number of tokens otherwise needed to get the model to perform the specialised task. Often, there is no need to offer in-context examples or explicit schemas, which translates into saved tokens. Sometimes, it can also distil the specialised task into a model smaller than the base one from which it was derived. Again, this ultimately translates into saved resources.

When fine-tuning, Colin suggests in the video that you start with a simple dataset without complex instructions, formal schemas, or in-context examples. All that is needed are natural language descriptions and the desired structure of the output.

Where fine-tuning excels

Fine-tuning works well when it emphasises pre-existing knowledge within the model, is used to customise the structure or tone of the desired output, or fine-tunes a highly complex set of instructions. The example given in the video is that of a text-to-SQL task. Base models like GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 already know everything there is to know about SQL, but they might perform poorly if asked about an obscure dialect of SQL. Fine-tuning is equivalent to telling the model to emphasise those aspects of its already present knowledge.

Where it won’t excel

Fine-tuning will not work to teach the model something new. And the reason can be thought of as the inverse of why fine-tuning excels in emphasising pre-existing knowledge. Consider the large datasets for some LLMs (like the-entirety-of-the-internet large). These training runs were so extensive that any attempt to use fine-tuning to inject new knowledge would be quickly lost in the pre-existing knowledge. If this is the objective, approaching the problem with RAG will be better.

Lastly, fine-tuning is a slow, iterative process. Preparing data and training requires a lot of investment, so it isn’t great for quick iterations.

Quality over quantity

It’s worth jumping to this part of the video for a humourous and cautionary tale on quality over quantity. In short, the takeaway from here is to ensure the fine-tuning data accurately represents the desired outcome; start small, confirm movement in the right direction, and then iterate from there.

And if you think fine-tuning a model on 200,000 of your Slack messages is a good place to start, maybe consider that a little longer.